The Maryland Department of Transportation recently announced yet another delay of the Purple Line’s opening to Winter 2027, five years after its initially planned completion in 2022. The 16.2‑mile light rail project, which will connect New Carrollton and Bethesda in Washington, DC’s northern suburbs is also way over budget.

The full extent of the Purple Line construction cost overrun is not fully known because it is embedded in an opaque Public Private Partnership (P3) relationship under which contractors are participating in the project. As originally planned in 2016, Maryland agreed to pay the contractor group $5.6 billion to build and operate the system for thirty years.

By 2022, contract amendments had increased this amount to $9.3 billion, but the portion of the increase attributable to construction cost overruns is not clear. The latest delay will add a further $425 million to the overall contract cost.

And this may not be the last delay or cost overrun that the project will experience. Maryland Transportation Secretary Paul Wiedefield was hesitant to commit to no more deadline extensions for the Purple Line opening. He considers it likely that further time and cost overruns can arise from testing the transit network’s systems, which evokes the eerie possibility of neighboring DC Metro’s $55 million project to fix wheels on its 7000‐series fleet.

While the Purple Line’s costs were greatly underestimated, its benefits are likely to be vastly overestimated. Total projected Purple Line ridership was expected to be 69,300 in 2040. This estimate, dating to August 2013, was reached based on the assumption that Washington metro area transit ridership would steadily increase over time.

The opposite has turned out to be the case, with the decade of the 2010s seeing a downward trend in DC Metro ridership. The pandemic and the work‐from‐home trend have further reduced ridership. DC Metro ridership in 2023 was only 50.6 percent of that of 2012, which would have been the most recent available ridership data at the time of the estimate’s publication. Notably, the Metro stations that lie on the Purple Line (New Carrollton, College Park, Silver Spring and Bethesda) now see even smaller proportions of their 2012 ridership than the system overall (32 percent, 40 percent, 45 percent and 41 percent, respectively).

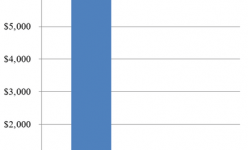

The Purple Line also is not expected to offer substantial time savings for riders between WMATA stations. The above chart compares the estimated Purple Line travel times between transfer stations to the DC Metro with the travel times on existing WMATA service at 5:00 p.m. on weekdays. In fact, in some cases, the Purple Line takes longer than existing transit options, such as the trip from Silver Spring to College Park, and the trip from Bethesda to New Carrollton, both of which would be trips more quickly made on the DC Metro. In fact, the only station pair that would see more than a 20 percent reduction in time due to the Purple Line is the trip from Bethesda to Silver Spring, which is a route well‐served by frequent bus service that takes at most 24 minutes during peak hour. While the current bus route from College Park to New Carrollton runs infrequently, under the no‐build option for the Purple Line the frequency of that bus would increase from every 30 minutes to every 10 minutes.

Despite these concerns, the project is very unlikely to be stopped, as it is more than 65 percent complete. The Purple Line serves as a costly reminder of what not to do. Maryland policymakers should reconsider other costly rail transit ideas, such as the Baltimore Red Line or an extension of the Purple Line further into Prince George’s County or Virginia.

If Maryland does go ahead with other projects. It should reconsider its P3 model. The main benefit of P3’s is the transfer of risk from taxpayers to contractors. In this case, it appears that the private participant is being allowed to shift cost overruns to the state agency. Under a best practice P3 agreement, the private entity would absorb cost overruns along with the impact of lower‐than‐expected ridership.

The author would like to thank Cato Research Associate Jerome Famularo for his help with this post.